Clashes That Shaped Civilizations

The ancient world was built on the ambitions of kings, generals, and empires. Their struggles were decided not only in courts and palaces but on dusty plains, in mountain passes, and across stormy seas. Some battles determined the survival of entire civilizations; others set the course of world history for centuries.

Here is an in-depth journey through some of the greatest battles of the ancient world—each one a turning point that echoes even today.

The Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE)

The Battle of Kadesh between Pharaoh Ramesses II of Egypt and Muwatalli II of the Hittite Empire was fought near the Orontes River in modern-day Syria. It is remarkable not just for its scale but for being one of the best-documented battles of antiquity, thanks to Egyptian inscriptions and reliefs.

Ramesses, eager to expand Egyptian influence into Syria, marched with a large army divided into several corps. However, Hittite spies misled him about the enemy's movements, and the Egyptian vanguard stumbled into a massive Hittite ambush near Kadesh. Hundreds of Hittite chariots thundered into the Egyptian ranks, creating chaos.

Ramesses himself was nearly overwhelmed but rallied his troops in a dramatic counterattack. Reinforcements from Egyptian allies, including Canaanite contingents, arrived in time to stabilize the line. Despite claims of victory by both sides, the battle ended in stalemate. Its true significance lies in the aftermath: the world's first known peace treaty, signed between Egypt and the Hittites. Kadesh proved that even in an age of conquest, diplomacy could be as powerful as war.

The Battle of Marathon (490 BCE)

When King Darius I of Persia sought to punish Athens for supporting revolts in Ionia, he sent a massive expeditionary force to Greece. The Persians landed at the Bay of Marathon, where they faced an Athenian army led by Miltiades.

Outnumbered nearly 2 to 1, the Athenians made a daring decision: rather than waiting behind defensive walls, they charged the Persians across the plain. Their heavily armored hoplites smashed into the lightly armed Persian infantry, while the wings of the Athenian line enveloped the enemy center. The Persians, unprepared for such ferocity, were routed.

The victory saved Athens from conquest and proved that Persia was not invincible. It also laid the psychological foundation for Greek unity in the wars to come. The legend of Pheidippides, who ran from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory before collapsing dead, gave rise to the modern marathon race—a lasting cultural legacy of this clash.

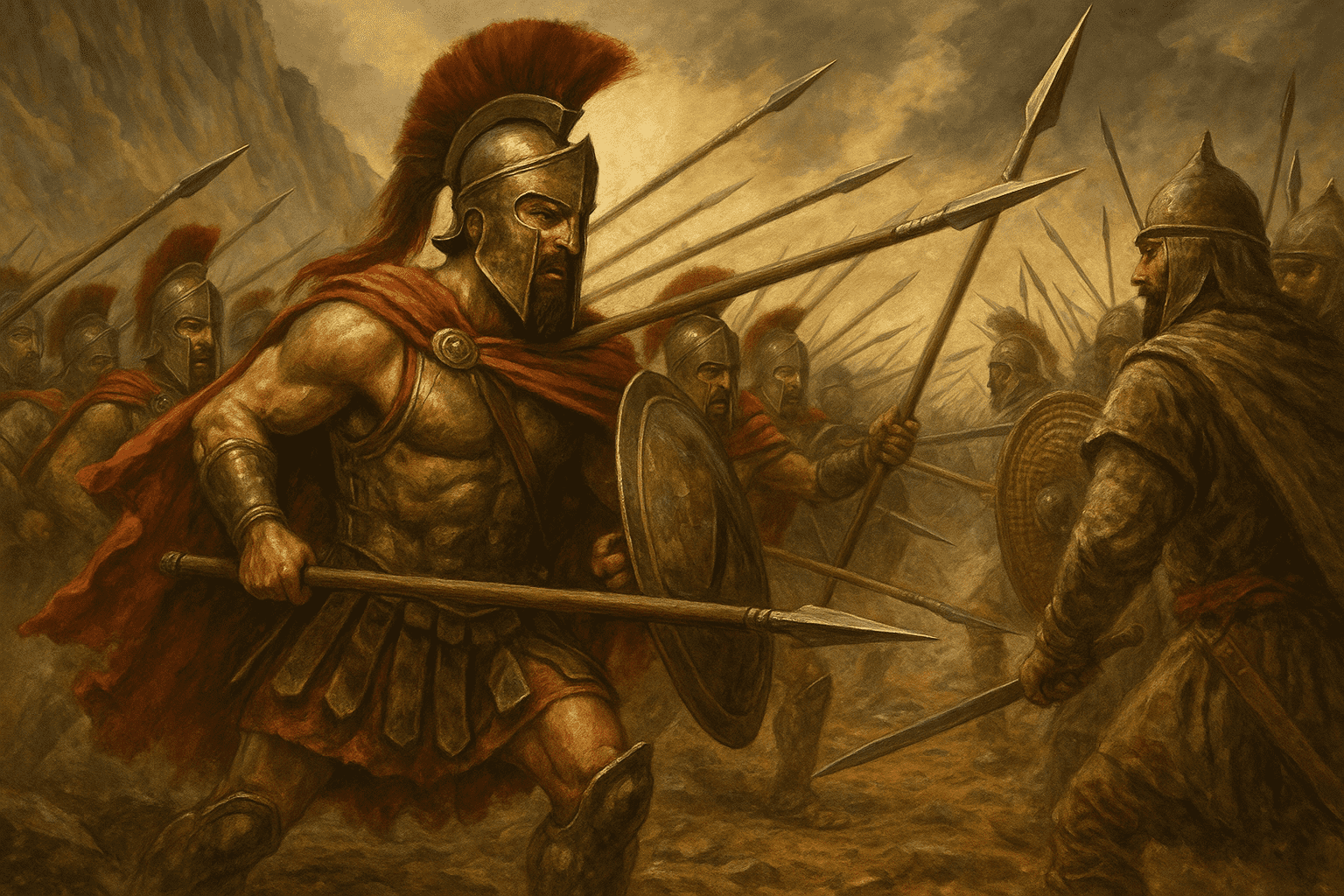

The Battle of Thermopylae (480 BCE)

Ten years later, Persia returned under Xerxes I with one of the largest armies the ancient world had ever seen. To block their advance into central Greece, the Spartans and their allies chose the narrow pass of Thermopylae.

Led by King Leonidas I, a small Greek force—famously including 300 Spartans—held off the Persian horde for three days. The terrain neutralized the Persians' numerical advantage, forcing them into narrow confines where Greek hoplites could fight effectively. Accounts tell of extraordinary bravery, with Leonidas and his men fighting to the last after being betrayed by a local guide who revealed a hidden path.

Though Thermopylae was a tactical defeat, it became a symbol of heroic resistance. It bought time for Greek cities to prepare their defenses and inspired unity against the invader. In later centuries, Thermopylae became a cultural legend, embodying the ideal of sacrifice for freedom.

The Battle of Salamis (480 BCE)

Immediately after Thermopylae, the Persians captured Athens and burned it to the ground. Yet the war was far from over. Themistocles, the brilliant Athenian strategist, lured the Persian navy into the narrow straits of Salamis.

The Greeks, with smaller and more agile triremes, rammed and boarded the cumbersome Persian ships, causing devastating losses. The geography of the straits prevented Xerxes from using his numerical superiority, and the Persian fleet collapsed in confusion.

The victory at Salamis was decisive. It forced Xerxes to withdraw most of his army and ensured that Greece would remain free. Many historians argue that Salamis saved Western civilization, as Persian domination of Greece could have prevented the flowering of classical culture.

The Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE)

When Alexander the Great faced the Persian king Darius III at Gaugamela, he was outnumbered perhaps five to one. The Persian army fielded war elephants, scythed chariots, and tens of thousands of cavalry. Yet Alexander's tactical genius turned the tide.

He deployed his forces with deliberate gaps, drawing the Persians into overextending their lines. When the Persian cavalry surged forward, Alexander launched his elite Companion Cavalry in a wedge formation straight at Darius. The Persian king fled the battlefield, and his army disintegrated.

Gaugamela marked the end of Persian dominance and the rise of Alexander's vast empire. Beyond military conquest, it ushered in the Hellenistic Age, when Greek culture, science, and philosophy spread across Asia and the Mediterranean.

The Battle of Cannae (216 BCE)

The Second Punic War brought Rome face to face with its most dangerous enemy: Hannibal Barca of Carthage. At Cannae, Hannibal faced a Roman force nearly twice the size of his own. Instead of retreating, he devised a brilliant trap.

Hannibal placed his weaker troops in the center and deliberately allowed them to be pushed back. As the Romans advanced, his strong cavalry swept around their flanks, while his African infantry closed in from the sides. The Roman army was completely encircled—the dreaded double envelopment.

The result was catastrophic: as many as 50,000 Romans were killed in a single day. Cannae remains one of the most studied battles in military history. Although Rome eventually recovered and won the war, the psychological impact of Cannae was immense, showing that even the mighty Roman legions could be crushed by tactical brilliance.

The Battle of Zama (202 BCE)

After years of struggle, Rome finally turned the tide of the Second Punic War. At Zama, in North Africa, Scipio Africanus faced Hannibal himself in a climactic showdown.

Scipio cleverly countered Hannibal's war elephants by creating lanes in his lines, allowing the beasts to pass harmlessly through. Roman cavalry, reinforced by allies from Numidia, crushed the Carthaginian horsemen and returned to attack Hannibal's rear.

Hannibal fought valiantly, but his army was overwhelmed. Zama ended Carthage's role as a major power and cemented Rome as the dominant force in the Mediterranean. It was the true beginning of Rome's imperial age.

The Battle of Carrhae (53 BCE)

Not all Roman generals were successful. Marcus Licinius Crassus, part of the First Triumvirate with Julius Caesar and Pompey, sought glory by invading Parthia. At Carrhae, however, he encountered disaster.

The Parthians, masters of horse archery, harassed the Roman legions with relentless volleys of arrows. Their heavily armored cavalry, the cataphracts, crushed Roman attempts to break free. The Romans, trained for close combat, were helpless in the open desert.

Crassus was killed—some accounts claim molten gold was poured down his throat as a grim symbol of his greed. The defeat at Carrhae revealed Rome's vulnerability in the East and foreshadowed centuries of struggle between Rome and Persia.

The Battle of Actium (31 BCE)

By the end of the Roman Republic, a power struggle raged between Octavian and Mark Antony, allied with Cleopatra of Egypt. Their fates were decided not on land but at sea, in the Battle of Actium.

Octavian's admiral, Marcus Agrippa, skillfully outmaneuvered Antony's fleet. Cleopatra, fearing capture, fled the battle with her ships. Antony, torn between command and loyalty to Cleopatra, followed her, leaving his fleet leaderless. The result was a decisive defeat.

Actium marked the end of the Republic and the birth of the Roman Empire, with Octavian becoming Augustus, Rome's first emperor.

The Battle of Teutoburg Forest (9 CE)

Rome's ambitions to expand deep into Germania ended in disaster at the Teutoburg Forest. Three Roman legions under Publius Quinctilius Varus were lured into dense woods by Arminius, a Germanic chieftain who had once served as a Roman officer.

Over several days of ambushes, the Romans were annihilated. Varus committed suicide, and the loss of 20,000 soldiers shocked the empire. Rome abandoned plans to conquer beyond the Rhine, establishing a permanent frontier.

Teutoburg was more than a battle—it was the moment when the Roman Empire recognized the limits of its expansion.

Conclusion – Battles That Shaped Civilization

From Kadesh to Teutoburg, these battles illustrate the fragility and resilience of empires. Some, like Marathon or Salamis, preserved fledgling democracies; others, like Gaugamela or Zama, created vast empires. Each clash was more than bloodshed—it was a hinge upon which history turned.

The strategies of Hannibal, Alexander, and Scipio are still studied in military academies today, while the heroism of Leonidas and his men remains immortal in cultural memory. These battles remind us that the ancient world was forged in fire—and its legacy endures in the modern one.