Famous Medieval Trials – Justice, Power, and Spectacle in the Middle Ages

Medieval trials were rarely just about justice. They were public performances—part legal proceeding, part political theater—where the accused could be saints or heretics, kings or peasants, witches or warriors. Often, the verdict was determined as much by power struggles and superstition as by evidence. These trials, many of them notorious, have left an indelible mark on history.

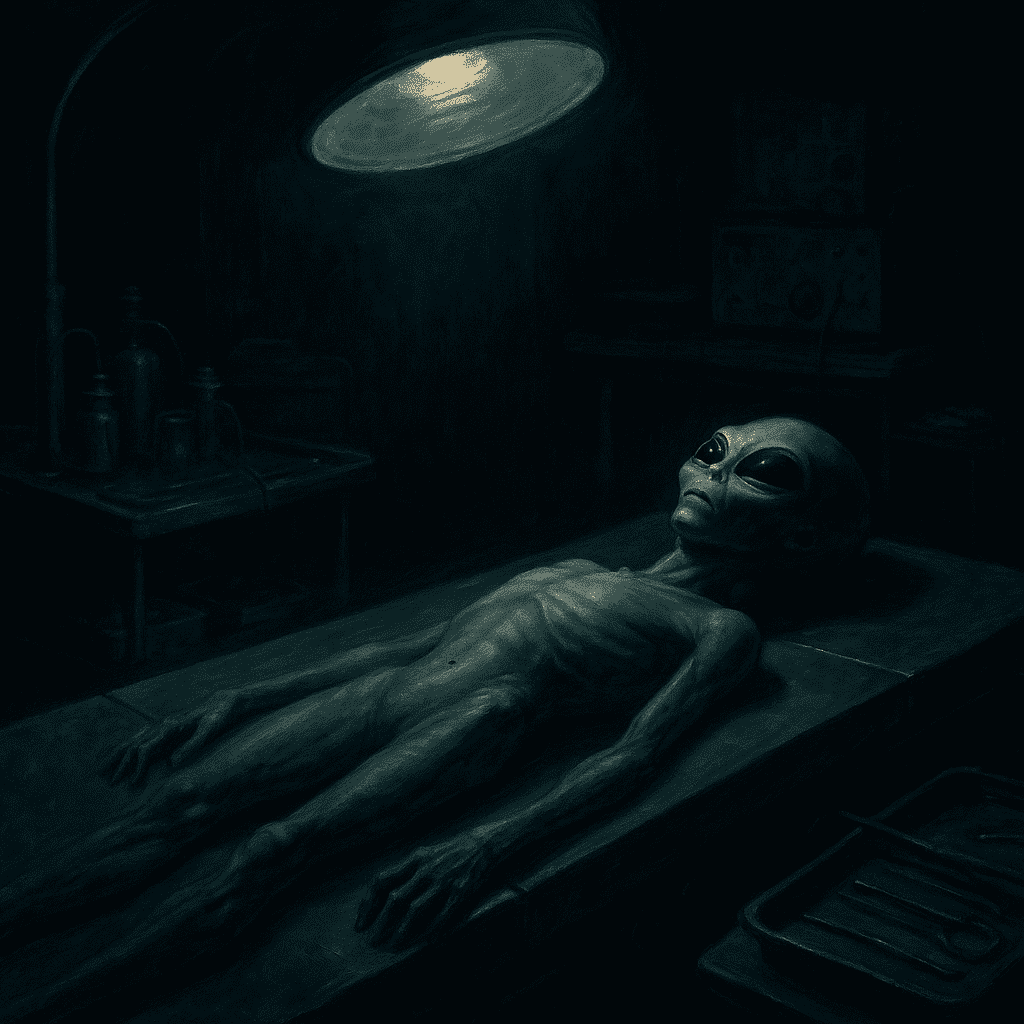

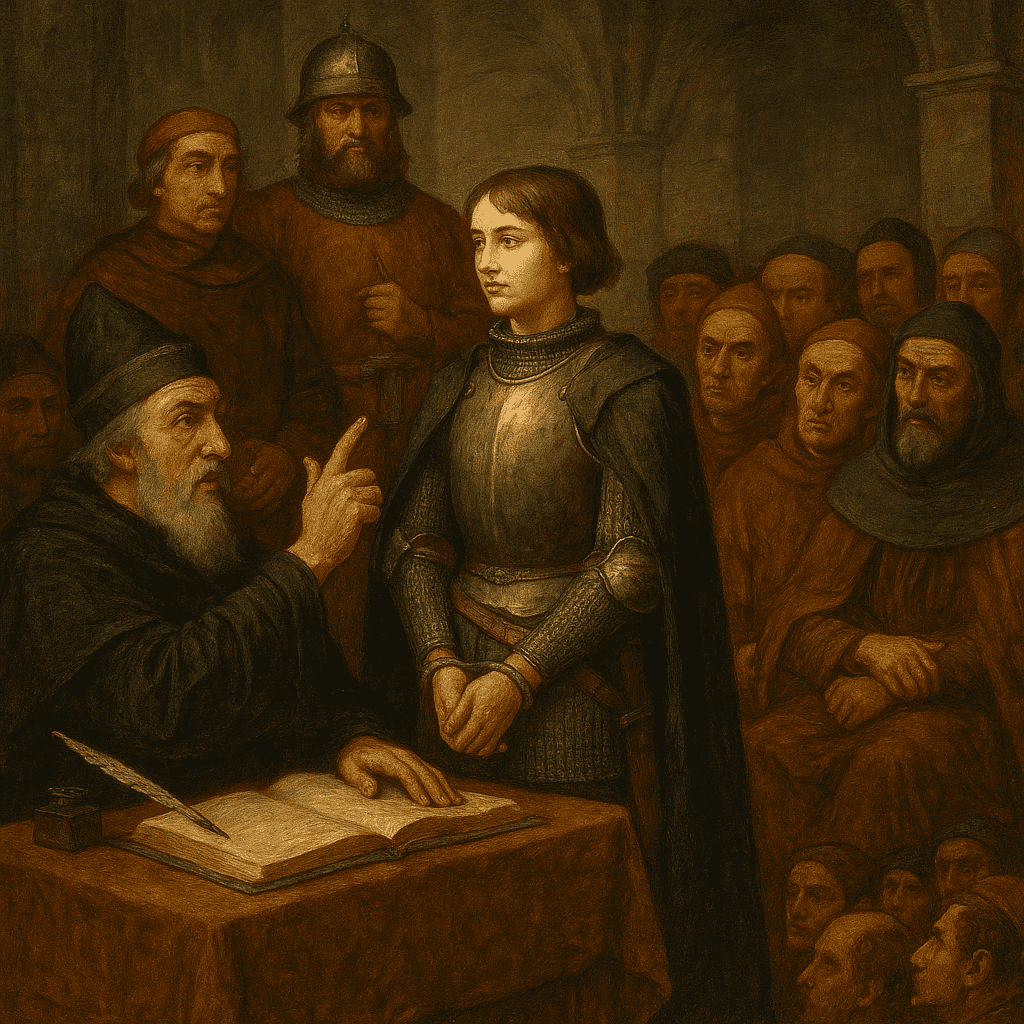

The Trial of Joan of Arc (1431)

Few medieval trials are as famous—or as tragic—as that of Joan of Arc, the young French peasant girl who claimed divine guidance in leading France against the English during the Hundred Years' War. Captured by Burgundian forces allied with England, Joan was tried in Rouen by a pro-English ecclesiastical court.

The charges ranged from heresy to cross-dressing (she wore male military attire). The trial was riddled with procedural flaws: witnesses were ignored, the court was biased, and Joan was denied legal counsel. Convicted and burned at the stake at just 19 years old, she was posthumously exonerated in 1456—and canonized as a saint in 1920.

The Trial of the Knights Templar (1307–1312)

The Knights Templar, once one of the most powerful military orders in Christendom, fell victim to the ambitions of King Philip IV of France. In 1307, Philip ordered the arrest of all Templars in France, accusing them of heresy, blasphemy, and corruption. The real motive? Philip owed the order enormous debts and coveted their wealth.

Under torture, many Templars confessed to outrageous charges—later recanted—but the damage was done. Pope Clement V disbanded the order in 1312. The last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, was burned alive in Paris in 1314, reportedly cursing both the king and the pope before his death.

The Cadaver Synod (897)

In one of the most bizarre trials in history, Pope Stephen VI put the corpse of his predecessor, Pope Formosus, on trial. The body, dressed in papal robes, was propped on a throne as the court read out charges of perjury and violating church law.

Predictably, the dead pope was found guilty. His body was stripped, mutilated, and thrown into the Tiber River. The grotesque spectacle shocked Rome and deepened political chaos in the papacy—a stark reminder that medieval justice could be as macabre as it was political.

The Trial of Marguerite Porete (1310)

Marguerite Porete, a French mystic and author of The Mirror of Simple Souls, preached a form of spirituality that bypassed the church hierarchy. Her teachings were declared heretical, and she was ordered to burn her book. She refused.

After a lengthy trial by the Inquisition in Paris, Porete was convicted of heresy and burned at the stake. Today, her work is recognized as an important text in medieval mysticism, and her trial highlights the dangers faced by those—especially women—who challenged church authority.

The Trial of William Wallace (1305)

The Scottish knight and freedom fighter, immortalized in legend and film, was captured by the English in 1305. Taken to London, Wallace was charged with treason against King Edward I—though he had never sworn allegiance to Edward—and with atrocities during the Scottish Wars of Independence.

Wallace's defense was simple: he could not be a traitor to a king he did not serve. It didn't matter. He was condemned, hanged, drawn, and quartered—a brutal execution meant to serve as a warning to others who defied English rule.

Medieval Justice: Faith, Power, and Fear

In the Middle Ages, trials were tools of control. They upheld religious orthodoxy, reinforced royal authority, and displayed the consequences of defiance. Whether fair or grotesque, they reveal a world where justice was inseparable from politics and where the courtroom could be as dangerous as the battlefield.