How the Roman Aqueduct Network Worked?

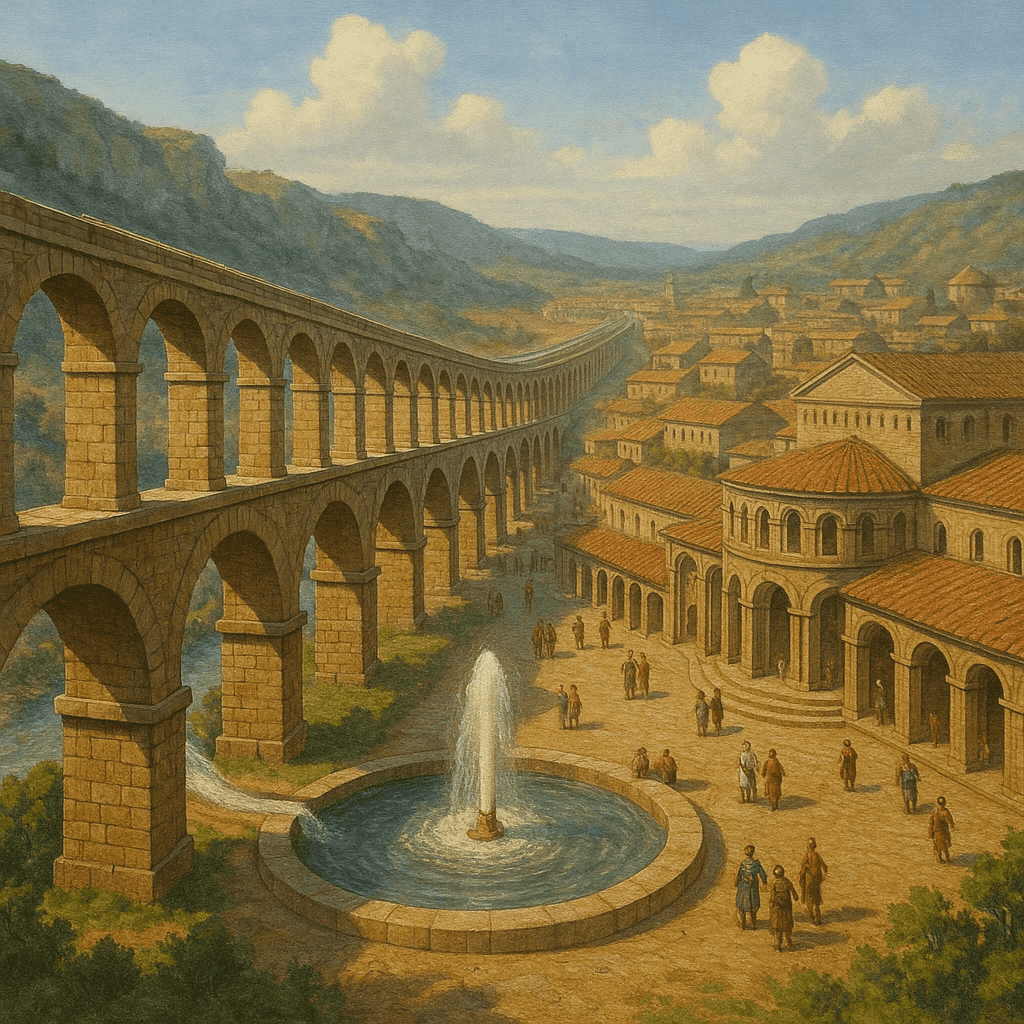

The Roman Empire is remembered for its legions, its law, and its monumental architecture. Yet one of its most remarkable achievements lies not in temples or arenas, but in the humble flow of water. The aqueduct system of Rome was a marvel of ancient engineering, providing the lifeblood of cities, fueling public baths, fountains, latrines, and even private households. At its height, Rome's aqueducts supplied the city with more than 200 million gallons of water per day—a feat unmatched for centuries.

Origins of the Aqueduct

Before aqueducts, Romans relied on the Tiber River, local springs, and wells for water. But as the city grew, so did demand. The first major aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, was built in 312 BCE under the censor Appius Claudius Caecus—the same official who began the famous Appian Way. This set the precedent for a system that would expand over the next 500 years.

By the late empire, Rome boasted 11 aqueducts stretching across hundreds of miles. Some, like the Aqua Marcia, carried water from springs nearly 60 miles away. Together, they sustained a metropolis of over one million inhabitants.

The Engineering Behind the Flow

Roman aqueducts worked on a simple principle: gravity. Water was collected from natural springs or rivers and channeled downhill along a carefully calculated gradient. The slope was subtle—just a few inches per hundred feet—ensuring a steady, controlled flow.

-

Underground Channels – Much of the system was hidden, with brick or stone conduits running beneath the earth to protect water from contamination and enemies.

-

Arcades and Bridges – Where valleys interrupted the path, engineers built the iconic stone arches we associate with aqueducts. The Pont du Gard in France remains one of the finest examples.

-

Tunnels – Roman surveyors bored through hills, sometimes meeting in the middle with remarkable accuracy, guided only by primitive tools and their knowledge of geometry.

Inside the conduits, the Romans lined the channels with waterproof cement (opus signinum) and installed settling tanks to remove sediment before the water reached the city.

Distribution in the City

Once inside the city, water flowed into large reservoirs called castella aquae. From there, lead or clay pipes distributed it to various destinations:

-

Public fountains ensured even the poor had access to clean water.

-

Bathhouses consumed vast quantities, reinforcing the central role of bathing in Roman culture.

-

Private homes of the elite could receive direct connections, a mark of wealth and privilege.

-

Sewers like the Cloaca Maxima carried away waste, helping Rome avoid the sanitation crises common in other ancient cities.

This system not only sustained life but also symbolized the power and sophistication of Roman civilization.

Maintenance and Management

The aqueducts were state property, overseen by officials known as curatores aquarum. A dedicated workforce of slaves, freedmen, and engineers handled repairs, cleaned conduits, and monitored water theft—an ongoing problem as people illegally tapped into the network.

Despite their durability, aqueducts required constant upkeep. Mineral deposits built up inside channels, narrowing flow, while earthquakes or invasions could damage bridges and pipes. Even so, many aqueducts functioned for centuries, some still serving communities long after Rome's fall.

Symbol of Power and Civilization

Beyond practicality, aqueducts were monuments of Roman authority. Their massive arches proclaimed the empire's mastery of nature, visible proof that Rome could bring water—and by extension, life—wherever it ruled. The system also reflected Roman values of public utility, civic pride, and engineering genius.

When the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century, many aqueducts fell into disrepair, and urban populations shrank. Yet their legacy endured. Medieval and Renaissance builders studied them, and modern water systems owe much to their principles. Some aqueducts, like the Aqua Virgo, were even restored to serve the fountains of papal Rome, including the Trevi Fountain.

Today, surviving aqueducts stand as silent witnesses to the ingenuity of Roman engineering—reminders that controlling water was as important to empire as armies or laws.