The Invention of the Railway – How Steel Rails Transformed the World

The railway is one of humanity's greatest technological milestones. More than just a mode of transport, it is a story of ambition, engineering ingenuity, and the way industrial progress reshaped entire societies. It changed how we travel, how we trade, and even how we measure time. Yet its invention was not a sudden breakthrough—it was a centuries-long journey from crude wooden tracks to high-speed electric marvels.

The Earliest Tracks – From Stone to Wood

The concept of guiding vehicles along a fixed path is far older than the steam locomotive. As early as the 6th century BCE, the ancient Greeks built the Diolkos across the Isthmus of Corinth—a paved stone trackway that allowed ships to be hauled overland between the Aegean and Ionian seas. It wasn't a railway as we know it, but it showed that channeling movement along prepared tracks could save time and effort.

Fast-forward to medieval Europe, and we find wooden wagonways in mines in Germany and England. These early systems used parallel wooden planks to guide carts pulled by horses, often with grooves to keep the wheels aligned. They were far more efficient than dragging carts over uneven ground, especially when moving heavy materials like coal or ore. However, wooden rails wore out quickly, warped in damp conditions, and limited the loads they could bear.

The Age of Iron – Stronger Rails for a Growing Industry

By the late 18th century, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, and demand for coal, iron, and manufactured goods was soaring. Engineers replaced wooden rails with cast iron, and later wrought iron, which could handle heavier traffic. This innovation dramatically increased the efficiency of mining operations and set the stage for mechanized rail transport.

The leap from horse-drawn wagons to steam power was inevitable. The mines already used stationary steam engines for pumping water, thanks to pioneers like Thomas Newcomen and James Watt. It was only a matter of time before engineers adapted steam engines to pull wagons directly.

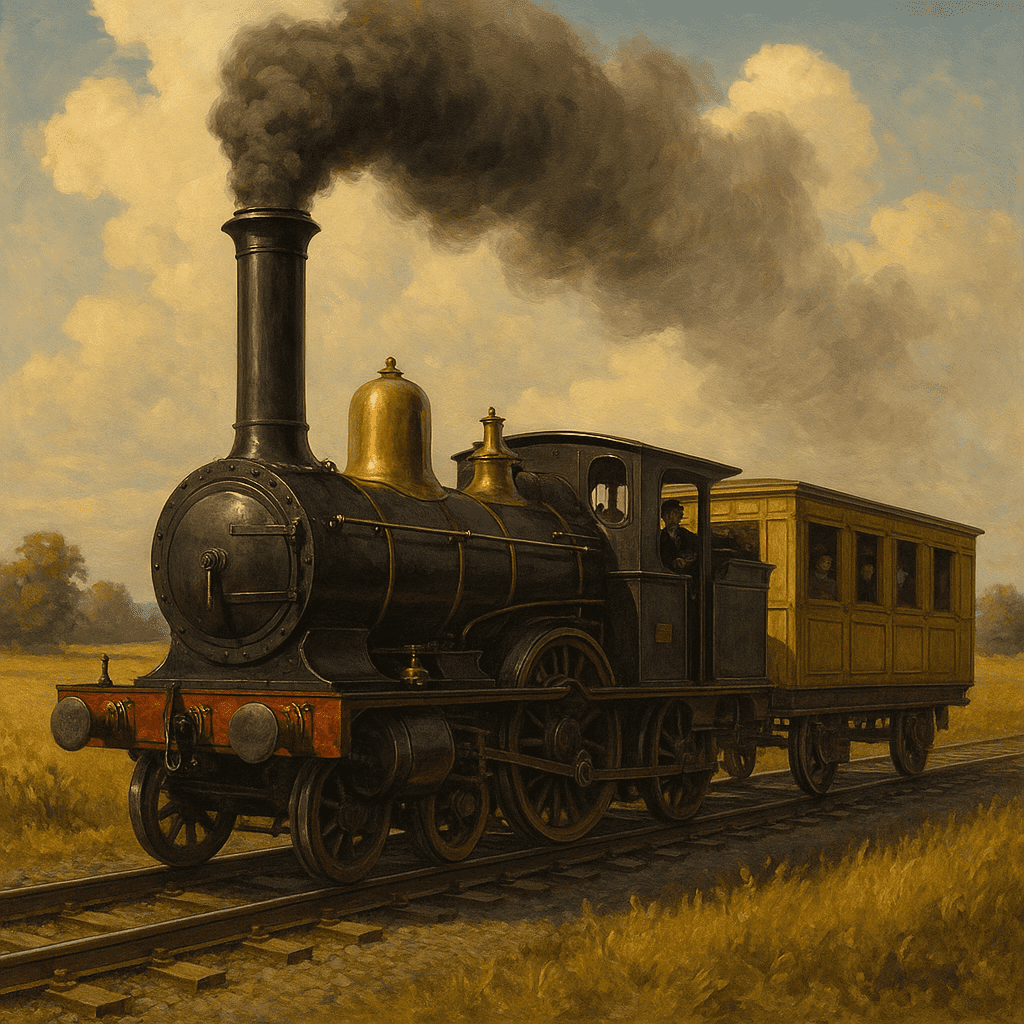

Richard Trevithick and the First Steam Locomotive

In 1804, Cornish engineer Richard Trevithick built the first steam locomotive capable of running on rails. Designed for the Penydarren Ironworks in South Wales, it successfully hauled a load of iron and passengers over a distance of nine miles. However, the locomotive's weight cracked the brittle cast-iron rails, and it was ultimately deemed impractical for regular use.

While Trevithick's design didn't immediately revolutionize transport, it proved the concept: steam power could move heavy loads on rails more efficiently than any animal.

George Stephenson and the Railway Revolution

The man who truly transformed the idea into a practical, global system was George Stephenson. Born in humble circumstances in 1781, Stephenson taught himself engineering while working in coal mines. In 1814, he built Blücher, a locomotive that hauled coal at the Killingworth Colliery. Over the next decade, he refined his designs, focusing on durability, efficiency, and standardized track gauges.

His breakthrough came with the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which opened in 1825. This was the world's first public railway to use steam locomotives, transporting both goods and paying passengers. The sight of Stephenson's Locomotion No. 1 pulling wagons of coal and carriages of people sparked public imagination.

Stephenson's crowning achievement followed in 1830 with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. It was the first line to rely entirely on steam locomotives and to be built with double tracks for bidirectional traffic. Its inaugural run, attended by politicians and dignitaries, demonstrated that railways were not just viable—they were the future.

The Railway Boom

The success of the Liverpool and Manchester line triggered what historians call "Railway Mania" in Britain during the 1830s and 1840s. Investors poured money into railway companies, and thousands of miles of track were laid across the country. Railways slashed travel times, making it possible to cross England in hours instead of days.

From Britain, the railway spread rapidly:

-

France opened its first lines in the 1830s, linking Paris with industrial centers.

-

Germany followed with the Nuremberg to Fürth line in 1835.

-

The United States began building railroads in the 1820s, culminating in the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869.

-

Russia started the monumental Trans-Siberian Railway in 1891, eventually stretching over 9,000 kilometers.

Transforming Time and Space

Railways not only moved people and goods—they changed the very way society understood time. Before trains, towns kept local time based on the position of the sun, resulting in a patchwork of timekeeping. Railway timetables made this impractical. In the 1840s, Britain adopted "railway time" standardized to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), a practice soon followed worldwide. This standardization paved the way for global time zones in the late 19th century.

Economic and Social Impact

The economic benefits were immense. Railways allowed industries to transport raw materials to factories and finished goods to distant markets with unprecedented speed. Farmers could sell perishable produce in cities hundreds of miles away. Tourism flourished, as ordinary people could now afford to travel.

Socially, railways shrank distances. They encouraged migration from rural areas to growing industrial cities, altered settlement patterns, and enabled national newspapers and postal services to reach every corner of a country.

From Steam to High-Speed

By the early 20th century, steam was giving way to diesel and electric locomotives. These offered greater efficiency, less maintenance, and higher speeds. In 1964, Japan introduced the Shinkansen bullet train, capable of speeds over 200 km/h, setting a new standard for passenger travel. France's TGV, China's high-speed network, and other systems have since pushed the limits even further, with trains exceeding 300 km/h.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy

The invention of the railway was not just an engineering feat—it was a turning point in human history. It bridged distances, fueled industrial growth, and forever altered patterns of commerce, migration, and communication. Even in the 21st century, with airplanes dominating long-distance travel, railways remain an essential, sustainable, and iconic part of the world's infrastructure.

The steel rails laid in the 19th century still echo with the sound of human ambition.