Women in Chivalric Orders – Forgotten Heroines of the Medieval World

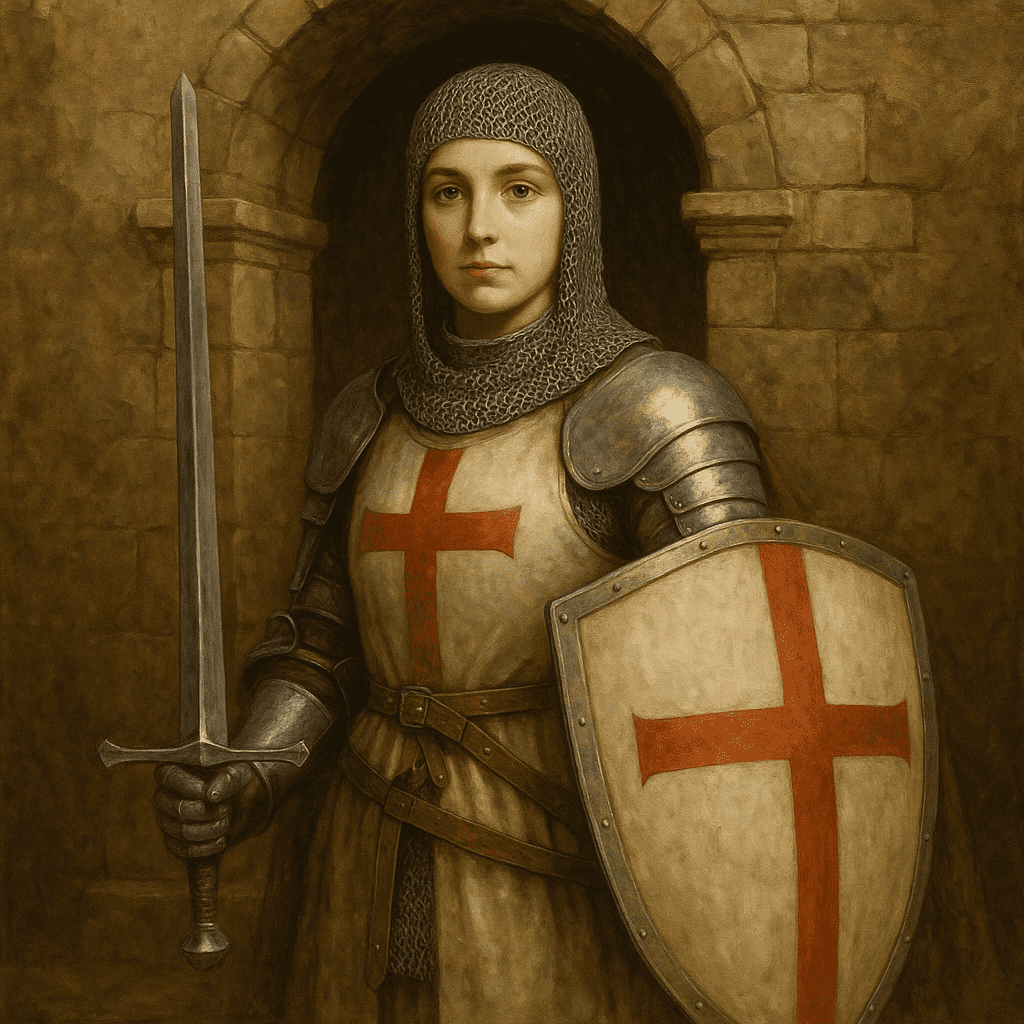

When we picture the knights of the medieval era, the image is almost always male—armored warriors on horseback, sworn to codes of honor and service. Yet history records a quieter, lesser-known reality: women were not absent from chivalric orders. Though their roles were often restricted by the social norms of the time, some women were active members, patrons, leaders, and even warriors within these prestigious institutions.

The Origins of Chivalric Orders

Chivalric orders arose in the 11th and 12th centuries, often in connection with the Crusades. Organizations like the Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller, and the Teutonic Order combined martial skill with religious devotion. Their missions ranged from protecting pilgrims to defending territories in the Holy Land.

While the orders were predominantly male, their survival and influence depended heavily on the support—and occasionally the leadership—of women.

Women in the Hospitaller Tradition

The Order of St. John (later the Knights Hospitaller) was unique in allowing the existence of affiliated female branches. Known as the Sisters Hospitaller, these women took vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience, just like their male counterparts. Their primary duties included caring for the sick and managing hospitals, but some also oversaw fortresses and estates.

In some regions, notably in Spain and Italy, women in the Hospitaller tradition held noble titles and administered land grants to fund the order's work. These positions gave them influence in both religious and political spheres.

The Order of the Hatchet – Catalonia's Warrior Women

One of the most remarkable examples of female participation in a chivalric order is the Order of the Hatchet (Orden de la Hacha), founded in the Catalonian city of Tortosa in 1149. During an attack by the Moors, the city's men were away, and the women took up arms—using whatever weapons they could find, including hatchets—to defend their homes.

In recognition of their bravery, the Count of Barcelona granted them the privileges of knighthood. They were exempt from taxes, could wear knightly insignia, and received the same honors as male knights. Although this order was short-lived, it stands as proof that women could be recognized for martial valor in the Middle Ages.

Noble Ladies and the Orders of Santiago and Calatrava

In the Iberian Peninsula, during the Reconquista, the Order of Santiago and the Order of Calatrava admitted women—not as frontline fighters, but as members with social and economic responsibilities. Noblewomen could join as commendadoras, living in convent-like communities, managing properties, and supporting military campaigns through resources and diplomacy.

Some of these women came from powerful families and leveraged their positions to influence political alliances, arrange marriages, and secure protection for Christian territories.

The Myth and Reality of Female Knights

While genuine female knighthood was rare, legends often filled the gaps left by the historical record. Figures like Joan of Arc, though not a member of a formal order, embodied the chivalric ideals of courage, faith, and loyalty. Her battlefield leadership during the Hundred Years' War challenged contemporary gender expectations and inspired both men and women.

Similarly, literary works of the Middle Ages, such as the tales of the warrior-maiden Bradamante in Italian epic poetry, kept the idea of the female knight alive in the cultural imagination—even if reality was more restrained.

The Legacy of Women in Chivalric Orders

Though sidelined in mainstream histories, women in chivalric orders left an enduring legacy. They demonstrated that the ideals of chivalry—service, honor, courage—were not exclusively masculine virtues. Whether as healers, defenders, administrators, or benefactors, these women played vital roles in the medieval world's military-religious institutions.

Today, some revived orders of chivalry still admit women as equals, paying homage to a history that was far more inclusive than legend suggests.